Currently 70 % of carbon emissions come from cities. In the future, cities need to be part of the solution, not the problem. Positive energy districts, or PEDs, are a rising concept for achieving this goal.

The basic idea of a PED is an area of a city that produces at least as much energy during the year as it consumes. However, a PED is not an island, rather a well-functioning and flexible part of the wider energy system. This concept revolutionizes the conventional practice of one-directional energy delivery though a pipeline from a power plant to consumers in a city. Now the city is transformed into a patchwork of producers, consumers and energy storages, all side by side and intertwined.

PEDs are a challenging goal but, given recent fast-paced development in energy technologies, they are now within our reach. Three basic things are needed to make PEDs possible.

1. First, developing a PED should begin by minimizing local energy needs. It makes no sense to build expensive and resource-consuming energy infrastructure to cover energy consumption that could be avoided in the first place.

The potential for energy efficiency can be, without exaggeration, considered to be enormous. For example, due to tightening regulations, in northern Europe typical new buildings now consume less than half of the energy for space heating compared to those in the year 2000. This improvement comes with minimal or no cost to consumers, as the relatively minor extra investment is covered with energy savings during operation. By no means has the potential for energy efficiency improvements been exhausted, rather only the lowest hanging fruit has been picked so far.

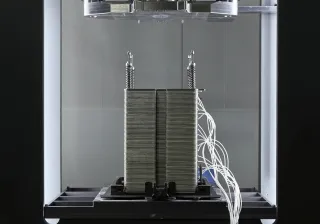

2. Second, the remaining energy consumption in a PED should be covered with local renewable energy production. This can mean various things such as using waste energy flows from electrical equipment and cooling, local solar energy production and various types of heat pumps. Planning a PED concentrates around local conditions, available resources and opportunities for reusing waste energy flows.

3. Third, smart planning and smart control are needed to make the energy system as a whole work. Loads should be matched so that energy is produced close to consumption both in space and time. For example, solar energy production is a natural companion of space cooling or refrigeration, as consumption typically peaks nicely at the same time as plentiful sunshine.

Similarly, smart control can be used to coordinate peak times of production and consumption. Electric cars, for example, are typically parked for long durations during the night and during the workday. This allows selecting optimal times for charging based on grid balancing needs. A lot of systems and equipment in buildings have similar leeway in timing their operation without causing any inconvenience.

These principles outline how the PEDs of the future can be achieved and some first areas are already here. For example, JPI Urban Europe has recently listed 28 pilot areas around Europe. However, even though these pilot projects are promising, it is clear that a great deal of challenges face any prospective PED developers.

Making sure all the necessary actors – such as the planners, builders, energy company and relevant departments of city government – work together efficiently towards a common goal is a daunting task indeed. Nevertheless, even if the challenge is great, so are the potential rewards of solving major parts of today’s sustainability and climate challenges.